The HALLOUMI cases : appetizer for the downfall of collective marks designating a geographical origin?

The collective word mark HALLOUMI owned by the “Foundation for the Protection of the Traditional Cheese of Cyprus named Halloumi” (Halloumi Foundation) is no stranger to European trade mark enthusiasts.

Earlier this year, after an appeal before the CJEU (C-766/18 P), the General Court already upheld its earlier judgment denying the likelihood of confusion between the collective word mark HALLOUMI and the sign BBQLOUMI, the latter serving to designate a cheese product commercialized by a Bulgarian company (T-328/17).

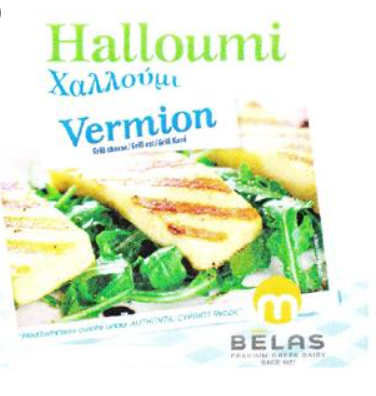

On 24 March 2021, the General Court delivered yet another setback for the Halloumi Foundation when it rejected the latter’s invalidity action against the below figurative trade mark application (T-282/19).

In doing so, the General Court appears to have severely limited the scope of protection of the HALLOUMI mark and, more in general, collective marks designating a geographical origin.

THE “HALLOUMI” COLLECTIVE MARK

“HALLOUMI” is a collective mark applied for pursuant to art. 74 EUTMR. The aim of this mark is to indicate that the cheese product protected by it originates from members of the Halloumi Foundation. The regulations governing the use of the mark provide that the right to use the mark is to identify cheese which has been obtained from fresh milk produced in Cyprus.

In recent years, the Halloumi Foundation has been very active in opposing the use of the word HALLOUMI by third parties, in particular by non-Cypriot companies, on the basis of the HALLOUMI collective mark. Most cases are still pending today. In the commented case, the Halloumi Foundation argued that the abovementioned figurative mark was likely to confuse the average consumer and also qualified as a bad faith application.

NO LIKELIHOOD OF CONFUSION

With numerous references to CJEU’s judgment in BBQLOUMI, the General Court recalls that although collective marks may serve to designate the geographical origin of goods (art. 74(2) EUTMR), this does not allow the registration of signs that are devoid of distinctiveness.

In that regard, the General Court finds, after an extensive analysis, that consumers will not associate the word HALLOUMI with anything other than the generic, descriptive name for a type of cheese rather than being a reference to its actual commercial origin, i.e. the members of the Halloumi Foundation.

Therefore, according to the General Court, there can be no likelihood of confusion between the signs in dispute. The relevant public, assuming that the common element is only weakly distinctive, will not establish a link between the contested figurative mark and the earlier collective mark. Consequently, the relevant public will at most establish a link between that mark and the cheese product it designates. Moreover, the General Court found that the marks at issue are similar only to a low degree as the word ‘halloumi’ plays only a secondary role in the contested mark, in particular in relation to what the General Court questionably considers the dominant words, ‘vermion’ and ‘belas’.

THE BAD FAITH

The General Court also addressed a point of law that was not raised in the BBQLOUMI case, namely the bad faith on the part of the contested trade mark applicant.

While a trade mark’s potentially descriptive nature does not as such prevent a finding that a trade mark is applied for in bad faith, the General Court, in the present case, considered that the use of HALLOUMI among the other word elements of the contested mark, must at most be regarded as the use of a word which is descriptive of the goods designated by that mark. Moreover, the General Court found that, taking into account the generic character of the word HALLOUMI, bad faith could not be inferred from a possible failure to observe the rules governing the use of the HALLOUMI mark.

CONCLUSION

The repeated harsh verdicts on the Halloumi Foundation by the European Courts show that the use by third parties of a sign designating a geographical origin is hardly combatable through collective marks, word marks in particular. The HALLOUMI cases demonstrate that when the proprietor of a collective mark, in particular those designating a geographical origin, is unable to provide sufficient proof of enhanced distinctiveness through use, the relevance of such mark is doomed to fade into oblivion.

Consequently, in view of the considerations above, associations like the Halloumi Foundation should consider whether applying for a collective trade mark is at all desired. After all, if possible, obtaining protection through a designation of origin (PDO) could prove much more effective. Such PDO can be enforced regardless of any likelihood of confusion and can be opposed against signs merely evoking the PDO without making use of the PDO as such.

In this respect, it seems that sunnier times are ahead for the Halloumi Foundation as on 29 March 2021, after a long-standing lobby battle, EU Member States finally agreed to register HALLOUMI as a PDO. This PDO registration may well be the much anticipated shield of protection to successfully oppose the unjustified use of HALLOUMI or other signs that evoke that designation. Those signs, such as the abovementioned figurative mark or the BBQLOUMI sign, might therefore not be safe after all.

This article first appeared on WTR Daily, part of World Trademark Review, in April 2021. For further information, please go to www.worldtrademarkreview.com. If you have any further questions on this specific topic, please contact Andreas Reygaert or Paul Maeyaert.