Louboutin hot on Amazon’s heels: does CJEU ruling on direct liability really make online platforms shake in their shoes?

In Louboutin v Amazon (Joined Cases C‑148/21 and C‑184/21), the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) delivered what some regarded as an early Christmas present to trademark owners seeking to enforce their rights online. In its decision of 22 December 2022, the CJEU finetuned the concept of direct liability under trademark law for online sales platforms.

The E-commerce Directive and the CJEU’s earlier case law on intermediaries

Under Article 14 of the so-called E-commerce Directive (2000/31), EU member states must ensure in their national laws that a service provider is not liable for the storage of any information provided by a recipient (so-called ‘hosting services’) where the provider does not have actual knowledge of the illegal nature of the content or where, upon obtaining such knowledge, the provider acts expeditiously to remove or disable access to the information. The rationale for this provision is to ensure that online service providers do not perform a general monitoring of infringements or, in the same vein, that the development of new activities and innovation in the internet sector is not hindered. The CJEU’s case law rendered prior to Louboutin v Amazon had always sought to reconcile the trademark owner’s exclusive trademark rights with the E-commerce Directive and found that internet intermediaries were not directly liable for trademark-infringing content provided by third parties on their platforms.

In Google v Louis Vuitton Malletier (Joint Cases C-236/08 to C-238/08, Paragraph 56 and following), the court had held that Google was not liable for trademark-infringing ads appearing in its search results through the selection, by the actual advertiser, of keywords (Google Adwords) identical or similar to registered trademarks. Similarly, in eBay v L’Oréal (Case C-324/09, Paragraph 101 and following), eBay allowed the use of signs by advertisers in online offers infringing third-party rights without eBay however using those signs in its own commercial communication. Only recently, in Amazon v Coty Germany (Case C-567/18, Paragraph 45 and following), the court again ruled in favour of the service provider by finding that Amazon’s own (physical) storage services of trademark-infringing goods on account of third parties did not mean that it ‘used’ those signs in its own commercial communication as it was the third party – and not Amazon – that subsequently put the infringing products on the internal market.

Denying direct liability does not mean that service providers are completely off the hook; in addition to notice-and-take-down proceedings under Article of the 14 E-commerce Directive, relief also remains possible by relying on indirect liability under the Enforcement Directive (2004/48), which allows a court to enjoin an intermediary from performing its services where those services are being used by the actual infringer to violate the trademark owner’s rights.

In addition, the safe harbours for online platforms do not apply where the platforms collaborate with one of the recipients of a service to engage in an infringing conduct which goes well beyond acting as a mere conduit, caching or hosting, as provided for in Articles 12, 13 and 14 of the E-commerce Directive. Hosting services, by their very nature, imply that the service provider is neutral, in the sense that its activity is merely technical, automatic and passive in nature, pointing to a lack of knowledge or control of the data stored (see Papasavvas (Case C-291/13), Paragraph 41 and the case law cited).

Amazon’s hybrid marketplace and integrated services

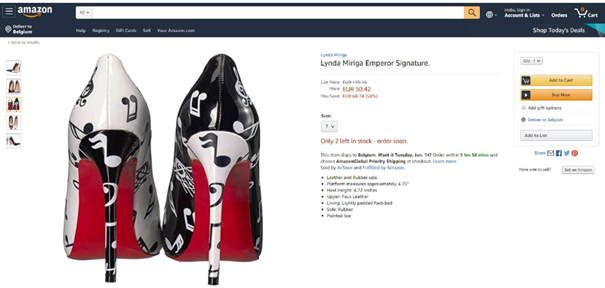

The activities at issue in the underlying case appeared to go beyond a mere intermediary (hosting) service. The specificity of Amazon’s business lies in the fact that it offers hybrid services, meaning that it does not only offer third-party products, but also own products which are uniformly presented or offered on its website using the same ‘Amazon’ logo. In addition, Amazon offers support or integrated services to third-party sellers consisting of the presentation of their advertisements, the stocking and shipping of the goods and the management of returns of those goods. Under such circumstances, the question arose as to whether an infringing offer of a third-party seller appeared, in the perception of the average consumer, to form an integral part of the platform’s communication and, thus, a part of Amazon’s own activity:

Screenshot of one of the offers targeted in the underlying case – “sold by Av3Nue and fulfilled by Amazon”

Decision

After analysing Amazon’s business model, the CJEU found that it cannot be ruled out that the average consumer on the Internet will be able to establish a material link between the infringing offer and Amazon itself, believing that Amazon bears responsibility for the offer and is marketing the goods in its own name and on its own account. Circumstances that contribute to creating such an impression are the following:

- First of all, the court noted that any online offer must be transparent to enable a well-informed and reasonably observant user to distinguish easily between offers originating, on the one hand, from the operator of that website and, on the other, from third-party sellers active on the online marketplace which is incorporated therein. The fact that Amazon implements a uniform method of presenting the offerings published on its website, displaying both its own advertisements and those of third-party sellers and placing its own logo as a renowned distributor on its own website and on all those advertisements, including those relating to goods offered by third-party sellers, and promoting them all without distinction as ‘bestsellers’ or ‘most popular’, may make it difficult to draw a clear distinction.

- Secondly, indiscriminate support services for both its own and third-party offers, such as customer care services (Q&A and management of returns), storage and shipping of goods, is likely to give the impression to a well-informed and reasonably observant visitor of Amazon that those infringing goods are being marketed by Amazon itself.

Comment

While some described the decision as groundbreaking, the ruling should not come as a surprise. Consumer confusion is at the heart of any infringement test in the court’s case law. Where the average consumer is unable to distinguish between the exact responsibilities and activities of, on the one hand, the sales platform and, on the other, the third-party seller, they may believe that Amazon is running the infringing offer in its own name. This will be a matter of fact to be assessed by the referring national courts.

In terms of practical significance, the ruling remains closely linked to the particularities of Amazon’s business model. Online platforms may face a direct trademark infringement claim only where they offer hybrid or integrated services. Such operators should make it very clear to consumers who they are buying from, reconsider whether to continue offering support services for third-party sellers or, in the alternative, implement a sound policing of their platforms. This case, therefore, does not represent a big shift in the court’s approach to the liability of intermediaries, but rather finetunes existing case law. To the extent that intermediaries merely provide hosting services used by third-party sellers, they continue to evade direct liability.

Interestingly, with this decision the court endorsed a liability regime similar to that of Article 6.3 of the newly adopted Digital Services Act (DSA). The DSA is intended to update the E-commerce Directive. According to the DSA, hosting activities remain out of the crosshairs unless the online operator presents the product in such a way that an average consumer would be led to believe that the information, or the product or service that is the object of the transaction, is provided either by the online platform itself or by a recipient of the service who is acting under its authority or control.

If you wish to receive more information or advice on related topics, please contact Jeroen Muyldermans or Paul Maeyaert.